24th September 2020

Is it really 12 months since the ignominious demise of Thomas Cook and the largest peacetime repatriation of British subjects since World War Two? Indeed, it is. Accompanied by a deep sense of shock and a searing Parliamentary enquiry, the company’s misfortune dominated the business pages for some weeks. The collapse of the household-name business cost the UK taxpayer some £520m with no doubt further and longer-term costs in social security and other related support payments as redundancies overwhelmed a loyal and seemingly capable workforce.

Why was it such a shock?

To an extent, the degree of shock at losing a company that had been a fixture on the UK’s High Streets was entirely understandable.

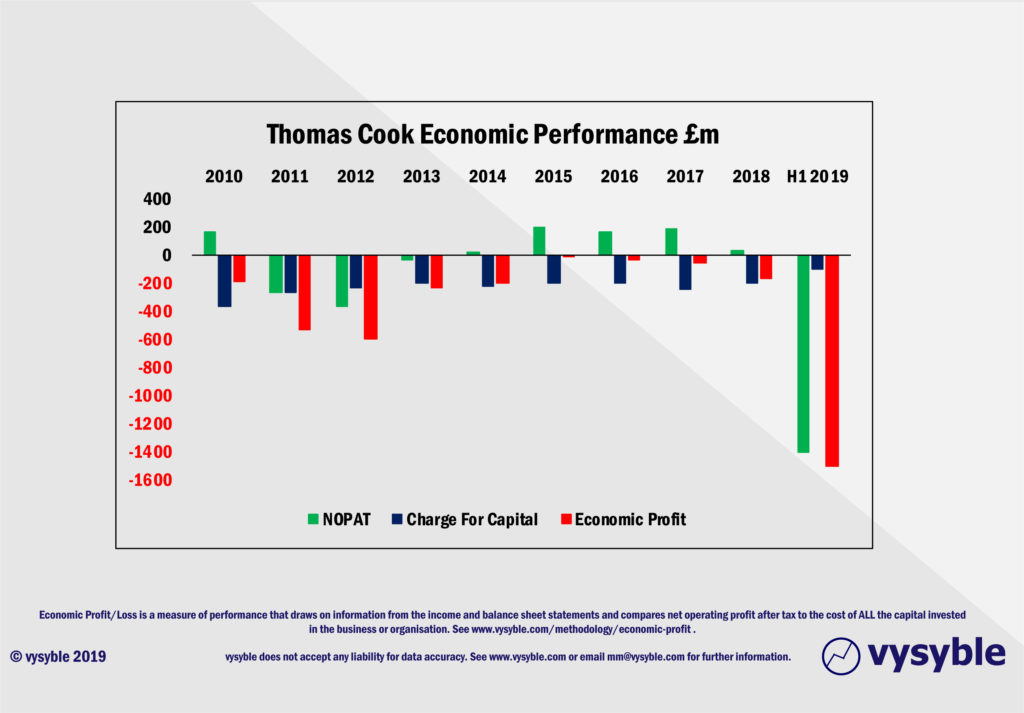

However, set out below is the Economic Profit (EP = net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) less a charge for ALL the capital used by the business) track record over the 9.5 years up to the point of the collapse of the company.

As we have described in previous material, whether the company is publicly quoted or a private entity, the Economic Profit measure brings the discipline of the capital markets inside the organisation.

When we apply it to Thomas Cook, we can see in the above chart that the strategies and decisions initiated by successive Executive Teams resulted in a situation where the company singularly failed to cover all of the costs of doing business in any of the nine-plus years in our analysis.

In other words, not a single instance of Economic Profit was achieved which means that the business failed to generate returns higher than the cost of the capital needed to run the business.

The level of value destruction over the period amounted to £3.65bn and when viewed through that lens it should arguably not come as a surprise that the business eventually collapsed.

Even though there were accounting profits, the economic losses were substantial. Why? Despite what the accounting profession would have you believe, equity capital is not free and when we apply a charge for ALL of the capital required by the business including the equity element, we finally get to see the true economic picture.

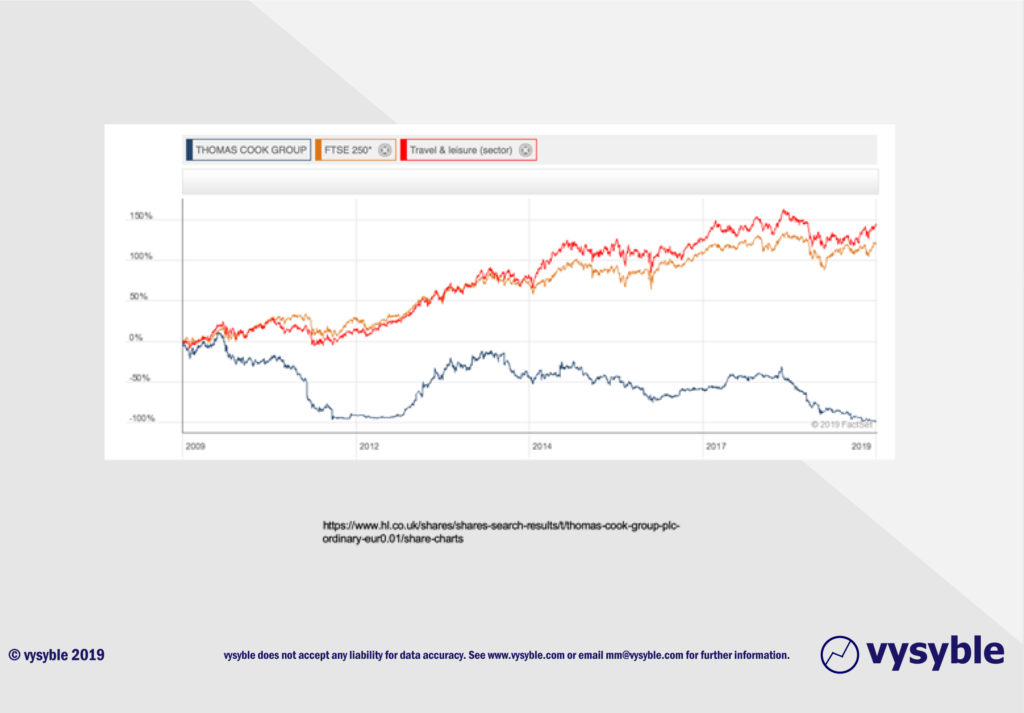

Much of the business commentary over the years was, in our opinion, worryingly positive about the company. However, the Economic Profit data strongly suggested that all was not well. Indeed, the capital markets were not fooled either as the chart highlighting Total Shareholder Returns values, over a period of 10 years, illustrates below:

Did the Excutive Team encourage the wrong behaviours?

Despite the trajectory of economic losses, the remuneration strategy for the Executive Team was running somewhat counter to the “governing objective” of a publicly quoted business which we believe, in the first instance, is the creation of shareholder value. Notwithstanding consistent economic losses and a falling share price, the CEO and the Executive Team were, quite legitimately but very unwisely, awarded significant performance related “bonuses.” In 2017, the CEO was awarded a bonus of £1.1m.

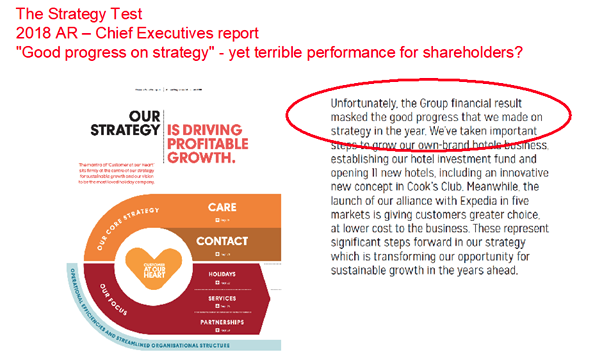

In the 2018 Annual Report, the CEO highlighted the latest strategy initiative… strong on sentiment but distinctly lacking in references to the creation of shareholder value.

So what?

A succession of Thomas Cook CEOs pursued strategies that were seriously misaligned with the objective of driving the value of the business. Thomas Cook’s company reports reveal some fundamental errors:

- Using the wrong objectives for the business. The Executive Team seemed obsessed by growing revenue instead of driving value – an all too common strategic error.

- The wrong financial metrics were deployed to monitor and manage the business including too much reliance on accounting measures such as EPS, EBIT and EBITDA rather than including economic measures which would have given a view of all of the costs of the capital deployed within the business.

- A minimal or no understanding of what drives value on the capital markets. The Executive Team’s strategies were clearly inferior to those adopted elsewhere in their sector as well as being fundamentally misaligned with value creation.… and yet it ploughed on.

- The Executive Team likely deployed a strategy development process based on flawed notions of “visions and missions”.

- The purchase of MyTravel in 2007 was a huge mistake.

- The incentive reward schemes were poorly conceived and may well have actively encouraged executives across the business to do things that ultimately destroyed value for shareholders.

Given all of the above and as we said before, the demise of the business should not have been a surprise.

A final word.

As you might have noticed elsewhere on our website and in our outputs including our media coverage, we have used the Economic Profit metric to uncover trends in many other companies and industries including certain aspects of English football.

Given the ongoing impact of the pandemic, we have found ourselves looking more frequently at the retail sector as the decline in footfall and the accelerated pivot towards online offerings increases the challenge facing many established businesses and their more-traditional financial models.

Currently, with total economic losses between 2016 and 2020 of just under £1.5bn, we are profoundly concerned about the medium-term existence of Marks & Spencer with the capital markets expressing a similar view. At the end of 2015, the company’s share price stood at £4.52 whereas at the time of writing (Sep 2020) the share price is hovering around £1.05; this is a fall of 76.7%.

Nobody is denying that times are challenging across the UK’s High Streets but over the same period Next plc’s share price has fallen from £72.90 to £61.54, down by a more palatable 15.6%.

The difference between the two companies is perhaps perfectly illustrated by their performance. Again, during the period 2016-2020, Next has produced an economic surplus of £2.6bn which when placed against Marks & Spencer’s economic loss of £1.5bn represents a performance differential of some £4.1bn.

In returning to the football space, we find our work is becoming centre-stage once again as the game grapples with a very tight financial squeeze with little room to manoeuvre. With the Premier League’s pre-Covid economic losses in the season 2018-19 of just under £600m against yet another record revenue level, the clubs are not in any sustainable financial fitness-level to cope with the current crisis.

With combined economic losses just shy of £2.8bn for the EPL clubs since 2009, the current situation is evidently not one that has suddenly appeared out of nowhere. A Parliamentary Committee and many MPs believe that the Premier League should subsidise or offer additional financial help to clubs in the lower leagues. But our stock observation is this: it is hard to envisage one group of economic loss-making clubs further subsidising another group of economic loss-making clubs. The consequences are likely to be as dramatic as they were with Thomas Cook.

As we often find without the application of value-based measures, the sums do not add up. And given that the world has radically, and some might argue, irreversibly changed in the 12 months since Thomas Cook ceased to trade, the focus on value is even more important now than ever before.

Follow vysyble on Twitter