11th September 2020

Once again, the start of a new season is upon us, but this time it threatens to be a season unlike any other as social distancing remains front of mind and government policy.

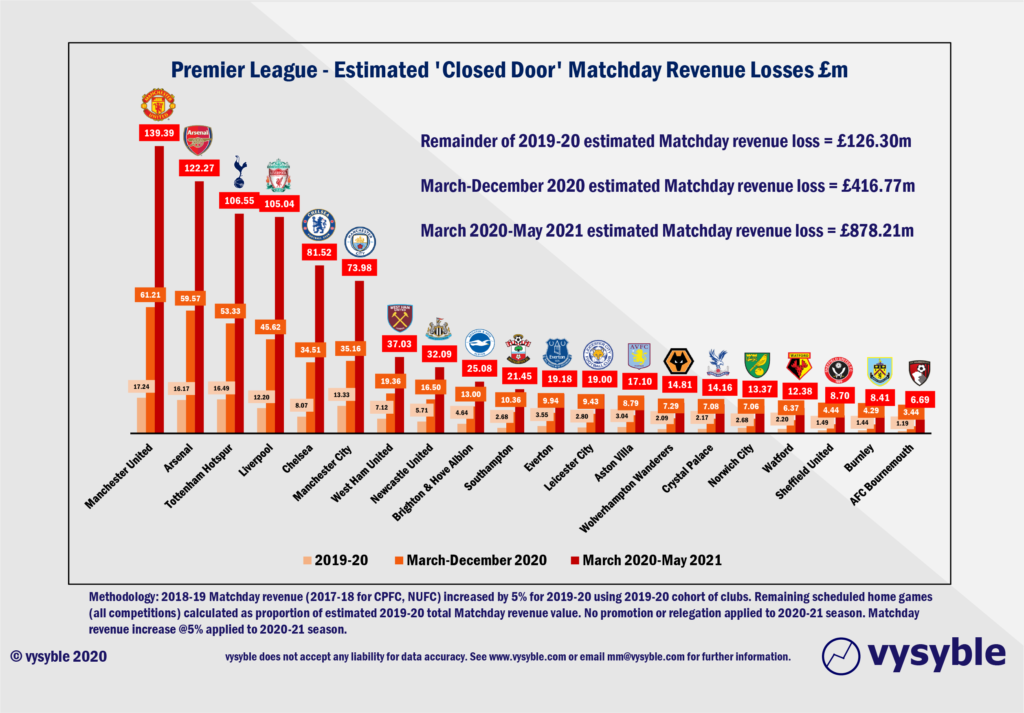

A game without crowds since March is regrettably displaying all the signs of distress that we have so often warned about in previous years as our data continually pointed to the underlying and long-term financial stresses in football’s financial model. Our ‘scaremongering nonsense’ (thank you, Mr Nick Harris) has become very real with Premier League supremo Mr Richard Masters recently imploring that football without crowds ‘can’t go on forever’ and citing a potential £700m hit to club finances.

But wasn’t it the case that Premier League clubs could quite happily survive without matchday revenue? A BBC article published back in August 2018 ran with the headline ‘Premier League: 11 of 20 clubs could have made profits in 2016-17 without fans at games.’ Indeed, one academic offered the following observation;

‘When you get a £120m pay-out from the Premier League for kicking a ball around, you can play in an empty stadium if you need to.’

Even in the last few weeks, the Financial Times published a gem of an article which highlighted the reliance of Premier League clubs on matchday revenue to the extent that ‘…unless fans return to stadiums soon, Premier League teams warn they face another lossmaking season.’ The article goes on to give a brief ‘insight’ into club finances with the following statement; ‘…teams are run on slender operating margins, so ticketing income is often the difference between making a profit and not.’

Really?

So, we thus have two conflicting views and both are some considerable distance away from a marginal offside decision in terms of truth and credibility.

The sad fact, as we have been at pains to point out since we first looked at football’s football model in late 2016, is that when all the costs of business are considered, it is largely a loss-making enterprise with little opportunity for value creation.

This is largely driven by excessive labour costs, poor regulation and an over-reliance on broadcasting income. Throw in a few owners with inflated egos and seemingly endless fortunes and the net result is a financial free-for all ‘ferment’ with the deepest pockets usually winning the trophies.

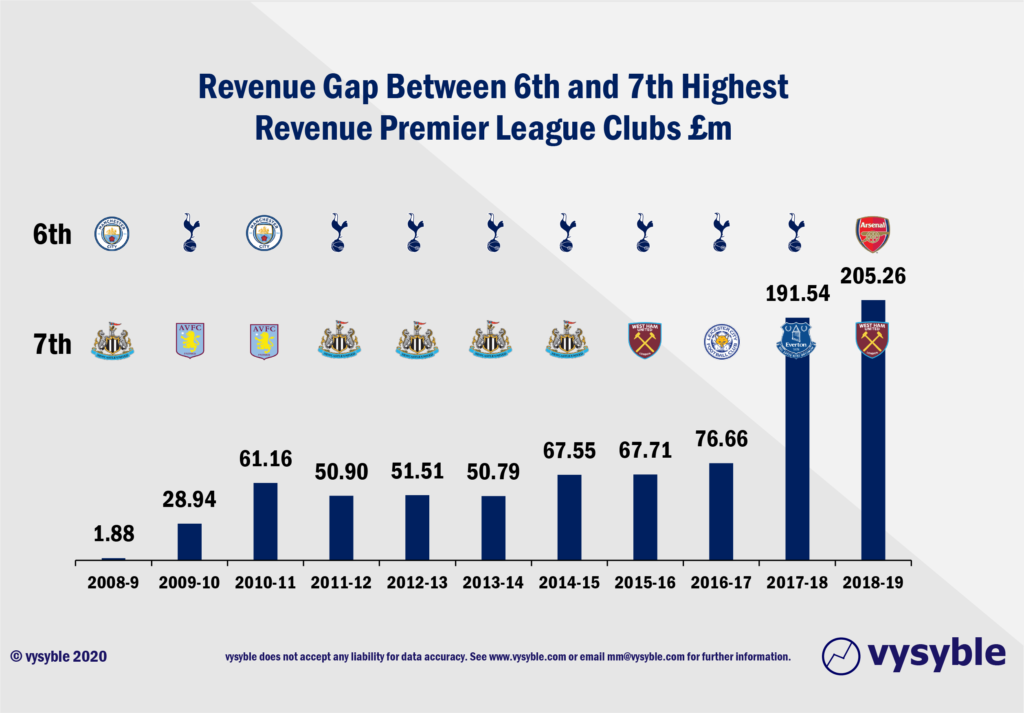

The problem with this type of dynamic is that the smaller and relatively ‘poorer’ clubs lose their ability to compete with the larger, ‘richer’ and more expansive operations. The gap between the rich and the less well-off tends to expand over time leading to inequality in competitive terms and invariably in regulatory matters too. This is clearly evident in the revenue trends between the 6th highest earning club in the Premier League and the 7th highest earning club but can also be seen in the financial land-grab by the top clubs in terms of international broadcast revenues.

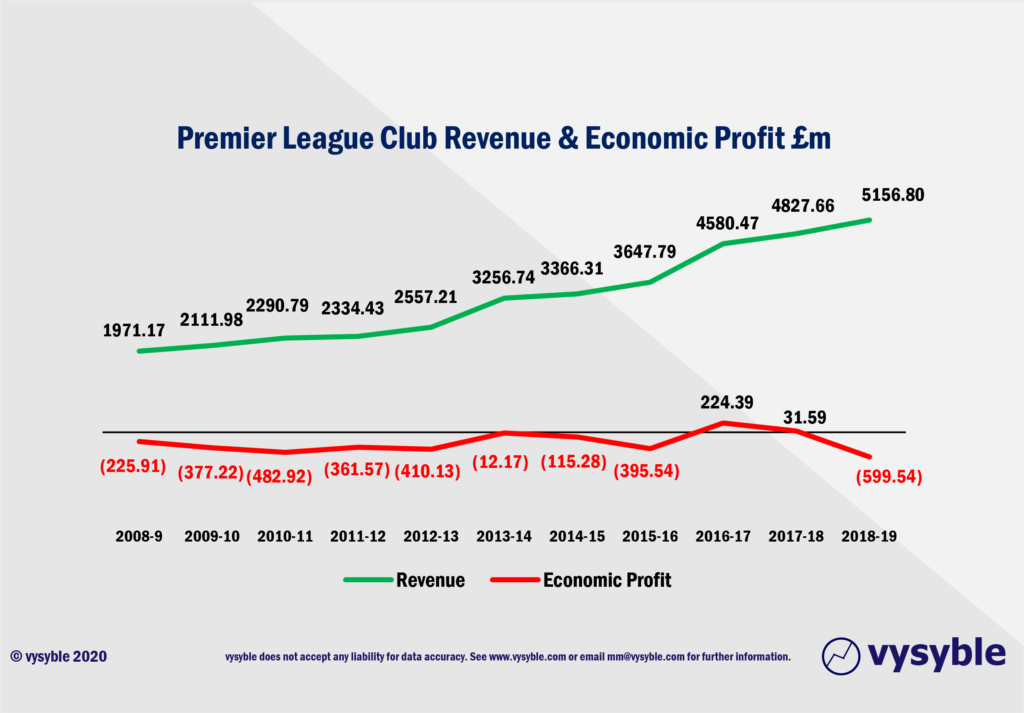

Returning to the matchday conundrum, the longer-term profit and loss profile clearly demonstrates that even with normal matchday revenues, the clubs have collectively made economic losses (when all business costs are considered) in 9 of the last 11 seasons where company accounts are available.

The afore-mentioned BBC article referred to the 2016-17 season, which was the first season of economic profit for the Premier League clubs on a collective basis on our watch (we have data going back to 2008-9). The wider financial context of the 2016-17 results perhaps suggested that the financial dynamic was changing, and in a more positive way.

However, the profit coincides with the first year of a then-record 3-year TV cycle. Pointers could have been gleaned from the previous 2013-16 TV cycle when losses were marginal in the first year but significant by the third year. Football clubs, it would seem, are creatures of habit in repeating the downward financial trend over the course of the 2016-19 TV cycle.

The Financial Times article seemingly fails to recognise the bigger picture financial dynamic. The notion that matchday revenue is the difference between profit and loss is frankly jaw-dropping when losses have been so consistent under normal conditions with normal crowds, normal revenues and normal costs.

When we consider the current picture on the eve of the new season, we take no pleasure in looking back on our reports and work which correctly highlighted the financial precipice casting a long shadow over the national game.

Yet here we are. It is highly likely that the record economic loss of £599.54m achieved by Premier League clubs in the 2018-19 season prior to the emergence of Covid-19 will be surpassed by the 2019-20 season given the hiatus in games between March and June resulting in a potential TV rebate of £330m (to be paid over an extended period), the loss of matchday revenue (between March and June) itself which we estimate to be £126m for plus penalties and rebates associated with numerous commercial contracts and agreements between clubs and sponsors.

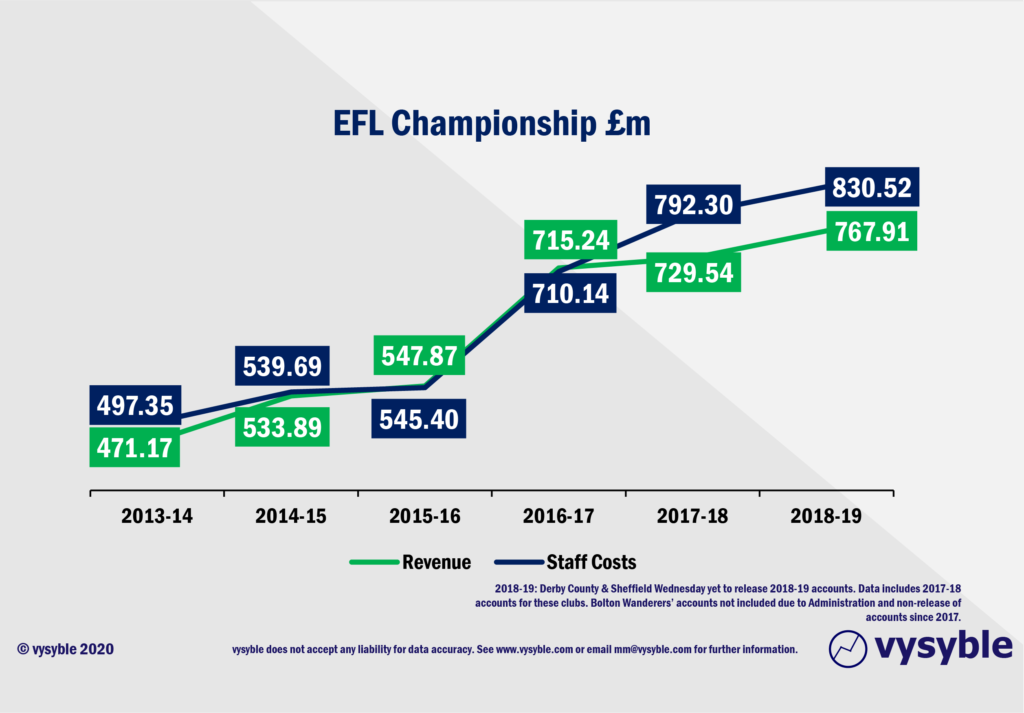

Continuing speculation surrounds a potential bail-out by the Premier League for the EFL but given the poor financial record of the senior division, particularly following a pre-Covid-19 £823m downturn in economic profit performance between 2017-19, it is hard to see how it could happen. Unfortunately, what we do see is increasing financial distress as Championship-level owners grapple with ludicrously high staff costs relative to revenue.

The ambition of Championship club owners to gain promotion and a slice of the apparently lucrative Premier League pot of gold which, as we have demonstrated, is largely loss-inducing seemingly knows no bounds. However, the unluckiest trio of clubs has to be those promoted into the Premier League for this coming season, namely Leeds United, West Bromwich Albion and Fulham.

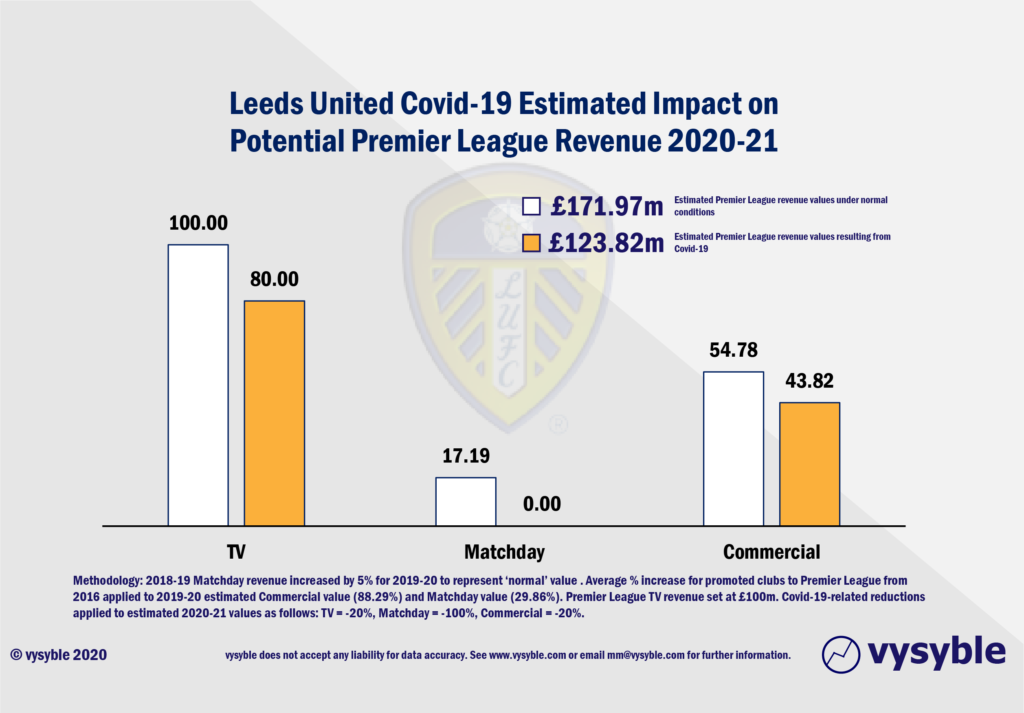

In Leeds United’s case, the 16-year absence from the top division has ended with a title-winning promotion following a near miss in the 2018-19 promotion race. Under normal circumstances, the club could look forward to a potential Premier League revenue of £170m+ given the average increase of almost 30% in Championship-level matchday revenues and an average 88% increase in commercial revenues enjoyed by promoted clubs since 2016. Whilst the club’s eventual Premier League finishing position determines the level of TV revenue, the club could expect to earn at least £100m from broadcasting in 2020-21.

Under Covid-19 with a rising infection rate and greater restrictions on the size of gatherings, that seemingly lucrative pot of gold will diminish in size and value, especially if social restrictions last until the end of the new season.

We estimate a TV/broadcasting revenue of around £80m although this could rise due to the club’s finishing position, with a commercial income of around £43-44m based on a 20% downward shift from what might be expected under normal circumstances. Of course, the matchday revenue could take a full season hit of an estimated £17m+.

Therefore, our estimation of the downward revenue impact is approx. £48m, with a potential ‘normal’ revenue of £171.97m being reduced to £123.82m ie a 28% reduction. Given the volatility of the circumstances that we all find ourselves in, our maths may well end up on the optimistic side.

Any business facing a revenue reduction of this magnitude will find the going tough. As the club has earned revenues of £178.37m but also achieved economic losses of £44.87m in the 5-year period between 2015-2019, the financial endeavour expended to achieve promotion with a likely and further economic loss in the club’s title-winning season has already been considerable. As we have stated many time before, promotion into the Premier League without a robust financial strategy is not a golden ticket. It is even less so now.

Leeds United may well be in a better position than most to weather the storm. However, for the majority of clubs it will be a financially chastening experience.

And as we continue to social distance and avoid ‘unnecessary’ social contact given current government guidance, the phrase that comes to mind is one from another competitive world, that of Game of Thrones…

Winter is coming.

vysyble

Follow vysyble on Twitter